?

METROPOLITAN DESIGN CETNER TRAVEL FELLOWSHIP: JAPAN 2007

CONCENTRATION: ARCHITECTURE AND CITY PLANNING

|

In the past two years, I have visited Japan three times in order to continue a sort of dialogue with the country. What began as a simple travel two years ago has evolved into deeper understandings of how this society operates, and how much potential there is for our own culture to be enriched. I traveled to Tokyo, Sendai, Osaka, Kyoto, Kanazawa and Fukuoka in search of architecture and physical relationships with surroundings. What I found in the process of this search was much more rewarding: a taste understanding.

Architecture and Japanese language are parallels whenever I travel to Japan. In order to understand more about the architecture, I must understand more about the language and how they express their own culture in their own native tongue. For this fellowship, my first stop in Japan was with Charlotte Anderson and Gorazd Vilhar in Tokyo. These two have been living in Japan for the last 20 years, working as freelancers studying the culture and taking photographs. Their guidance continues to help me formulate a way of seeing, a way of asking questions to further understand my surroundings.

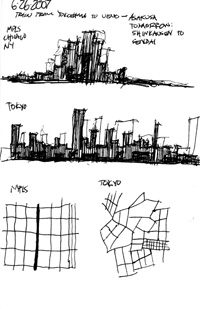

After only two weeks observing Tokyo, I traveled to Sendai to visit Toyo Ito's Sendai Mediatheque. This trip to Sendai was my fist time leaving Tokyo, first time riding a bullet train, and the beginnings of my voyage into the unknown. The speed of the Shinkansen, or bullet train, is not unlike the rush you get from an airplane, although one never leaves the ground. By departing one of most dense metropolis' in the world and traveling to a smaller city within Japan, I was able to distill ideas and relationships of how a city comes together and works.

From Sendai, I returned to Tokyo for a few days, gathering research at architecture exhibitions and museums, and after a few days, continued south to Osaka. There, I met with Doctor Toshiya Okayama from the Osaka Institute of Technology. During our discussion, I was able to gather a great overview of Osaka and Fukuoka city planning, as well as research on the city planning of Germany and Japan, which is Doctor Okayama's primary focus.

Moving quickly was the only downside of my travels, and soon it was time for the next city. I trekked over to Kyoto after only three days spent in Osaka. Although Kyoto was not on my original itinerary, I vowed to travel there because of the high recommendation of Gorazd Vihar. I was able to visit Katsura Rikyu, Uji Byodoin, Kinkakuji, the Imperial Palace, Kiyumizu shrine, and many others along the way. It is important when visiting a temple or a shrine to not get absorbed in the architecture alone, but to sense what is around the structure. If you were to look at an arial photo of Japan, there are pockets of complete development (such as Tokyo and Osaka) surrounded by vast forests and mountains. Much is true with these sacred places in Kyoto as they are surrounded by the green mountains that circle the city. Once one embraces the surroundings, it is possible to understand that the true beauty of this architecture is not its permanence, but the ephemeral qualities of the seasons acting on the sacred building, the aging, the constant balance to return to nature. In cities such as Tokyo and Osaka, this process of natural deterioration is actually fought, and the average life-span of a typical building is only 20 years before it is deconstructed and rebuilt.

It was sad to depart from Kyoto after only three days, however, Kanazawa was calling my travels back to contemporary architecture and a world renowned garden. I had learned about Kanazawa from an Exhibition in Tokyo at the National Art Center (designed by Kisho Kurokawa) on building skins. In Kanazawa, there stands the newly completed 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art designed by SANAA, architects Kazuyo Seijima and Ryue Nishizawa. Kanazawa is a city that is simply magnificently planned and presented. The city itself has a rich tradition with many ancient temples and a system of irrigation canals that runs through the entire city. Yet it is clearly ahead of its time in the contemporary beautification of the city through such things as pedestrian friendly sidewalk layouts and the amazing Kanazawa train station which looks like a giant steel and glass sunami flowing into a large wooden Torii gate. The Kanazawa Kenrokuen garden is one of the most visited in Japan by the Japanese people, and it is adjacent to the SANAA museum. this juxtapositions the garden and the museum is a constant reminder of the balance between the ancient and the new, and the western influences on Japanness, as Arata Isozaki would describe it.

Tokyo, Sendai, Osaka, Kyoto, and Kanazawa were all precedent studies for understanding Fukuoka, also known as Hakata, which is the final stop on the Shinkansen that goes from Kyushu through Tokyo all the way to Hokaido. Fukuoka is an established city only three hours from Pusan, Korea by ferry. The majority of cities in Japan have a decreasing population, but Fukuoka's population is steadily increasing. In the past twenty years, much time and effort has been spent on the city planning and overall design of Fukuoka. I decided to meet with six well know architects in Fukuoka in order to understand how their efforts effect the city. I met with and interviewed Kyoko Matsuoka, Koichiro Oba, Toshiaki Tanaka, Kaoru Suehiro, Matsuyama Masakatsu, and Shoei Yoh. Much of my findings were based on the observations and facts put forward by Andre Sorensen's The Making of Urban Japan, in addition to the writings to Toyo Ito, Kisho Kurokawa and Arata Isozaki.

How circumstance our lives truly are. I often walked out of a train station in Tokyo and never turned around in an effort to orient myself with something new where ever I went - often resulting in finding myself severely lost or ending up at a destination I once thought was unobtainable. I attempted the same in Fukuoka, and was always able to find my way without turning around. I spent a month here, and was able to feel at home which I feel is necessary in order to understand any city or place. Many of the observations I made in Fukuoka can be applied to my true home town of Minneapolis, and I feel this connection I have with Japan has the potential to extend beyond a two month travel, but a conversation between cultures that can extend at many scales and improve the quality of civilized spaces and institutions around the world. I recently returned to Japan to celebrate New Years in Tokyo and meet with friends in Fukuoka and Kyoto. I plan to return to Fukuoka to work for an architecture firm in May, 2008, and continue this conversation of cultures.

|

|

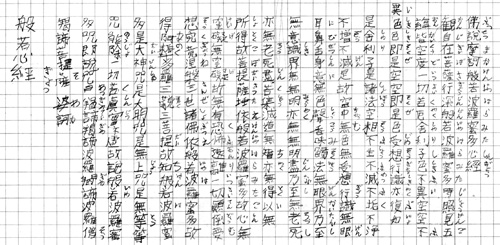

MAKING THE URBAN FIBER VISIBLE

This travel fellowship consists of visits to Tokyo, Sendai, Osaka, Kyoto, Kanazawa and Fukuoka to study the urban fiber in the context of programmatic relationships to public buildings and public spaces, specifically architecture and the street. In Minneapolis, we find our way by streets and numbers. In Japan, buildings are numbered in the order they were erected. The city becomes less a grid of numbers and streets, but a series of spatial meanings and programs. People walking around the streets of Tokyo or Osaka therefore have a mental map of the city and the relationship of structures. Much like the Japanese writing system Kanji (Chinese borrowed image-like writing system), the city becomes a dialogue and a layered mesh of visual understandings for each individual.

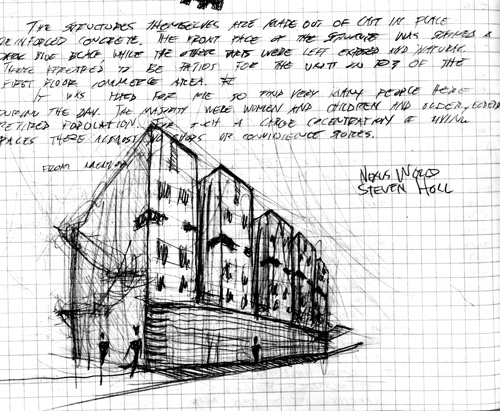

Fukuoka is highly studied by students that attend The University of Tokyo and all over Asia for its recent contemporary architecture and risky city planning. Well known architecture in Fukuoka includes Nexus World by Rem Koolhaas and Steven Holl, a new central park by Toyo Ito, works by Kazuo Shinohara, Michael Graves, Ryu Kosaka, Arata Isozaki, Cesar Pelli, Aldo Rossi, Kisho Kurokawa and the list goes on.

The Twin Cities Metropolitan area has a much more spread out, car structured urban fabric. However, in time Minneapolis will become denser and expand into the suburban ring, new passageways will form, and the suburbs may be given an urban identity that is lacking. Anchoring institutions such as the Guthrie, the Downtown Public Library, and the Walker art center are beginning to describe a city ‘without street names,’ and one that is more visually oriented by pedestrians and public transportation.

Fukuoka is a prime example of how architecture can visually ground a city using train stations, parks, public buildings, and anchoring institutions. Therefore, Fukuoka was focused on specifically in this fellowship. Tokyo, Sendai, Osaka, Kyoto and Kanazawa are used for gathering information and precedents for a full study of Fukuoka.

I was submerged into both architecture and Japanese language, while in the process articulating the social and visual interactions that take place in the advanced orderly chaotic visually structured Japanese city. This is a brief overview of what I was seeing and thinking when I was studying Japan.

FELLOWSHIP OBJECTIVE

My name is Evan Hall and I am Senior in the University of Minnesota undergraduate Architecture BS program studying Japanese. I have been taking intense Japanese language courses for four years and traveled to Japan in the summer of 2006. I wanted to gain a glimpse of the architecture and language I had been studying in textbooks. What I found was something far from the illusions of textbooks and photographs: Japan is ordered chaos. As one might imagine, I experienced a slight sensory overload of information. The text from my textbooks became three-dimensional and intertwined. Architecture and Japanese were separate in my mind before my first trip to Japan, and during my travels everything was real. It is the process of learning architecture and Japanese apart from each other inn the classroom and then immersing myself in them both at the same time, that chaos issued into more structured ideas of a city and relationships.

In Spring of 2007, I applied for and was granted the Metropolitan Design Center’s undergraduate travel fellowship to return to Japan and continue my observations. This fellowship, which took place over the summer of 2007, is a continuation of my travels to Japan in 2006, a continuation of attempting to combine architecture and language in interesting and creative ways.

Kenzo Tange describes an architecture that is ephemeral, changing, paced with society, connected to the future and socially structured. Toyo Ito blurs the idea of what architecture is, and how to better articulate how the digital world and the physical are connected. Tadao Ando uses heavy, solid concrete to craft weightless light and shadow. Those are three examples of ideas flowing throughout the streets of Japan’s cities, but how do these drastically different programs interact, change, and work. Japan does not have a street naming system, but uses landmarks and stations. Landmarks are often structures that define spaces around them. It is in this way that the entire city becomes a visually connected system for every user instead of a street number and address.

Within my design studio, I attempted to capture this otherwise invisible architectural knowledge and structure it. For example, while studying Kenzo Tange in studio, I choose to use concrete and glass to describe a building’s program to demonstrate how program is always flowing, a continuous process. Concrete flows, as does molten glass, as if they were still in their untouched state of sand, yet their properties are vastly different when defined. The urban fabric that Ito describes in his writing is not visible, but layered behind screens of linguistic interactions and architecture. Language and Architecture. I have been studying these two together for my college career trying to make connections and formulate ideas to better understand how different programs interact in this urban fabric, as well as to help formulate my own ideas about architecture.

Evan Hall

|